Every life begins with a single cell. This divides again and again until a complete organism is formed. But how exactly this fundamental process takes place in some animals has been a mystery until now. Researchers at the Technical University of Dresden have now discovered a surprising mechanism that fundamentally changes our understanding of cell division.

The discovery concerns animals with particularly large egg cells. Sharks, birds, reptiles and zebrafish, a type of fish, are among them. The cells in their embryos are huge and full of yolk. This yolk serves as a food supply. However, it is precisely this that makes cell division complicated.

The role of scaffolding structures

Normally, cells divide according to a simple principle. A ring of the protein actin forms in the center of the cell and tightens like a string. "With such a large yolk in the embryonic cell interior, there is a geometric restriction," explains Alison Kickuth from the Physics of Life Cluster of Excellence. She is the first author of the study published in Nature. The classic lacing ring cannot close completely. Nevertheless, the division succeeds.

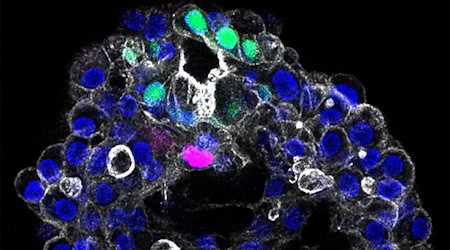

The research team examined zebrafish embryos. Using precise laser cuts, they severed the actin ring during division. Surprisingly, the ring continued to constrict. This showed that it is supported over its entire length. The scientists discovered another important structure in the process. Microtubules are tiny tubes inside the cell. They form the scaffolding of the cell. The experiments showed that these tubes stabilize the actin ring. Without them, the ring collapses.

A mechanism like a ratchet

The inside of the cell, the cytoplasm, changes its consistency rhythmically. In certain phases, it becomes solid and provides support for the actin ring. In other phases, it becomes liquid. The ring can then constrict more deeply. This change is repeated over several cell cycles. The ring contracts bit by bit. "The temporal ratchet mechanism fundamentally changes our understanding of cytokinesis," emphasizes Jan Brugués, head of the study.

"Zebrafish are a fascinating special case, as cytoplasmic division in their embryonic cells is inherently unstable," explains Alison Kickuth. The cells divide particularly quickly in order to overcome this instability. The division takes place over several cell cycles by alternating between stability and liquefaction. The discovery could apply to many egg-laying species. It shows how adaptable nature is. For science, this opens up new perspectives for research into biological processes.