Every year, over two million people worldwide die from liver diseases. Until now, it has been difficult to study such diseases in the laboratory. Animal experiments only reproduce the human liver inaccurately. Simple cell cultures cannot mimic the complex processes in the organ. A research team from Dresden has now found a solution. The scientists have developed a three-dimensional model of the human liver that consists of real patient cells.

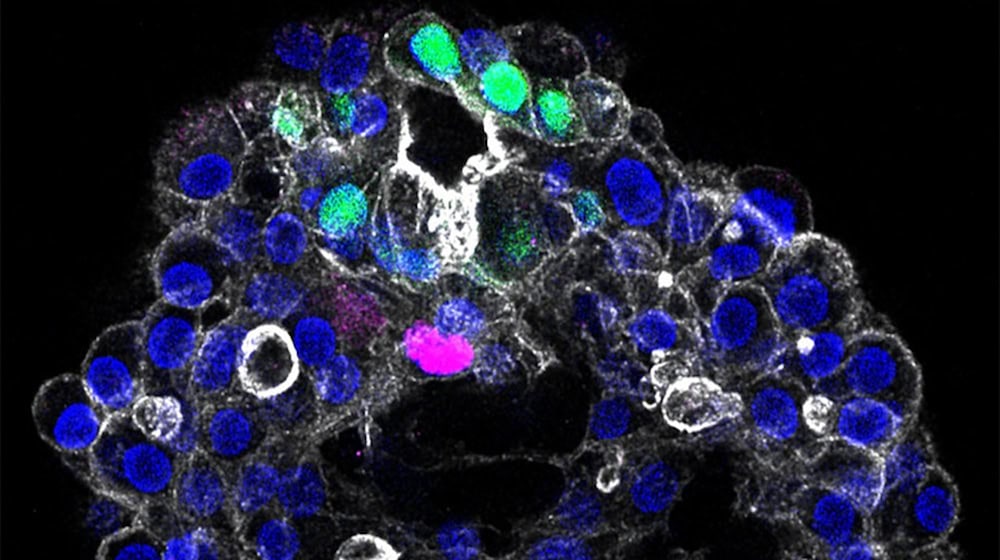

The team led by Meritxell Huch from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden has combined three different liver cell types. Hepatocytes form the main part of the liver. Cholangiocytes line the bile ducts. Mesenchymal liver cells are connective tissue cells. These three cell types organize themselves into a lifelike structure in the Petri dish.

For the first time with bile ducts

The development was a real team effort. In addition to the Max Planck Institute, the University Hospital Dresden and the University Hospital Leipzig were also involved. Yohan Kim, one of the lead authors, explains: "When we received the tissue from the patients, we first had to separate the individual cell types and multiply them in a Petri dish before we could reassemble them."

Doctoral student Sagarika Dawka developed the model further. "Our study presents the first complex human liver model outside the body that has bile ducts," she says. These bile ducts are important because if they become blocked, liver damage occurs. The researchers have already created a biobank with cells from 28 patients.

Testing new drugs

Meritxell Huch heads the research group. "With our new model, we have mastered a major challenge. Until now, it was not possible to reconstruct the multicellular organization of periportal liver tissue and the cellular interactions outside the living body," she says. The researchers can now observe how different cells interact and how diseases develop.

The liver models can be used to test the efficacy and safety of new drugs. This could reduce animal testing. And because the models consist of cells from individual patients, personalized treatments are possible. "Our novel liver models have the potential to change the way we study and treat liver diseases," says Huch. The study was published in Nature.