Every human being begins as a single cell. But how does it become a complete organism with billions of specialized cells? This question has long occupied biologists. Researchers at TU Dresden have now deciphered a crucial mechanism. The first cell divisions in the embryo function through a sophisticated game with instability.

Jan Brugués' working group at the Physics of Life Cluster of Excellence investigated how embryos organize themselves in the earliest developmental phase. This involves a critical moment. The fertilized egg cell divides rapidly into many individual cells. However, complete cells with their own membranes do not yet develop. Instead, the cell material is gradually divided into sections. "From a physical point of view, this instability should disrupt embryonic organization," explains Brugués. "Nevertheless, the development proceeds with impressive robustness."

Filamentous structures as conductors

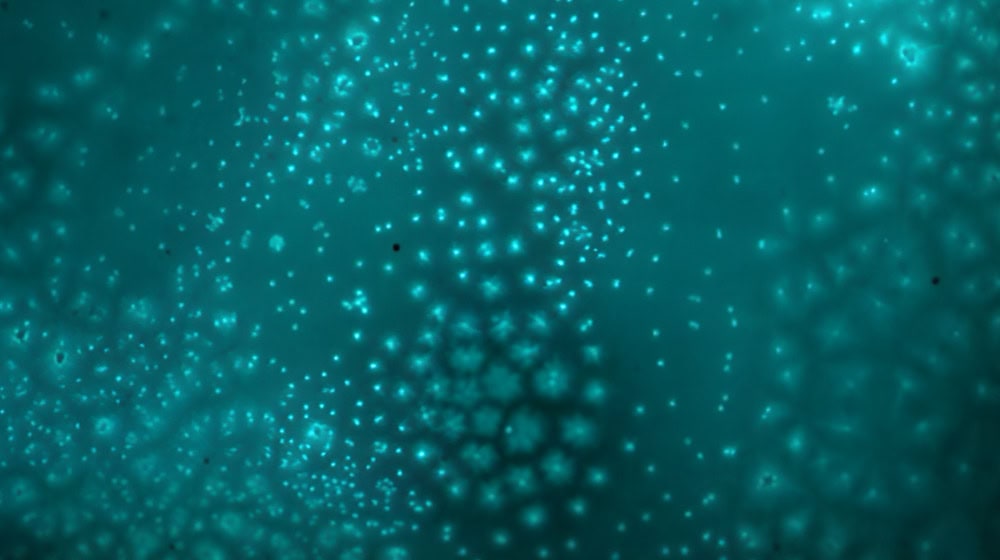

The scientists discovered the main players in this process: microtubules. These thread-like structures are part of the scaffolding of the cell. They assemble into star-shaped structures, so-called asters. These stars spread out inside the cell and thus divide up the cell material. The researchers used extracts from African clawed frog eggs for their experiments. Surprisingly, these extracts can also organize and divide independently outside of living cells.

The team combined experiments with frog extracts, observations on living embryos and mathematical models. This revealed that the microtubule stars are inherently unstable. They do not simply grow next to each other. Instead, they penetrate each other and sometimes merge. This could upset the entire division.

Each species has its own solution

Different animal species have developed different strategies to deal with this instability. Zebrafish and frogs rely on speed. "The timing of cell divisions is precisely coordinated with the onset of instability," says Melissa Rinaldin, first author of the study. The divisions occur so quickly that the stars can spread out before they fuse.

The fruit fly chooses a different path. It forms fewer new microtubule stars. This results in smaller, more stable structures. These gradually fill the cell material over several divisions. Even small changes in the physical properties of the microtubules explain major differences between species.

The Dresden findings have far-reaching implications. The regulation of microtubules could have served as an evolutionary switch. It enabled different species to follow different developmental paths. The results are also relevant for medicine. Changes in microtubule dynamics could play a role in the development of healthy tissue. They may also be involved in diseases such as cancer.