When electricity from the wind and sun is not needed, it has to be stored somewhere. Large batteries that are permanently installed in electricity grids could store this energy - as cheaply, safely and long-lasting as possible. However, many such storage systems lose power faster than expected during operation. Researchers from Dresden have now investigated why.

The team from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) has studied a special type of battery: the sodium-zinc molten salt battery. It works at around 600 degrees Celsius. At this heat, the metals sodium and zinc are liquid. This allows them to move particularly well inside and react quickly. This makes the battery powerful, but also difficult to control. "These systems have great potential because sodium and zinc are cheap and readily available," says Dr. Norbert Weber, who is coordinating the EU SOLSTICE project at the HZDR. "At the same time, there has so far been no clear understanding of why the cells lose so much performance during operation."

Look without opening

The problem: you can't simply unscrew a battery that runs at 600 degrees. However, when it cools down, the structures inside change. "Our battery is completely liquid. What happens there is highly dynamic," explains Martins Sarma, first author of the study. "But we can't simply open a battery during operation to take a look."

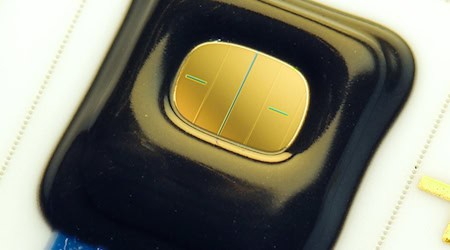

The solution is X-rays. Using a method called operando X-ray radiography, i.e. an X-ray image taken while the battery is running, the team looked directly into the active cell for the first time. The images showed how sodium, zinc and the hot molten salt inside move during charging and discharging.

The separator as a weak point

A so-called separator, a porous separating layer, is located inside the battery. It is designed to prevent sodium and zinc from coming into direct contact with each other and combining in an uncontrolled manner. However, it is precisely this separator that can become a problem at high temperatures. Dr. Natalia Shevchenko, who studies batteries at the HZDR, describes it like this: "You can imagine it like a sieve in which the material gets stuck. Over time, more and more active zinc is lost." The zinc accumulates in the separator and loses contact with the electrode. It can then no longer contribute to storing electricity. The battery ages more quickly.

Further experiments showed that the zinc remains more mobile without a separator. However, the battery then partially discharges itself, even without a connected consumer, because sodium and zinc can react with each other more easily. The results show that the separator is not a harmless component, but has a major influence on service life and efficiency.

The HZDR team is now working on optimizing the structure of the battery and better controlling the movements of the liquid components. The aim is to create robust and affordable large-scale batteries that will one day be able to reliably store large amounts of wind and solar power.

Original publication:

M. Sarma, N. Shevchenko, N. Weber, T. Weier, Operando characterization of Na-Zn molten salt batteries using X-ray radiography: insights into performance degradation and cell failure, in Energy Storage Materials, 2025.